Next Tuesday a few of us at Microsoft Research are hosting a day-long dialogue to discuss the interminglings of data and social/civic life. We’re bringing together a mix of social theorists, commentators and policy advisers with the hope of drawing out possibilities for doing policy making (as well as technology design) differently. Our preamble for the event follows (a printable PDF can be downloaded here):

Dialogues on data, policy and civic life

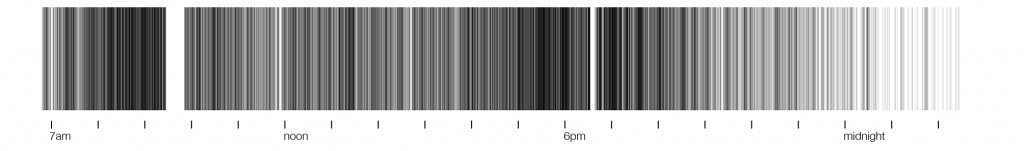

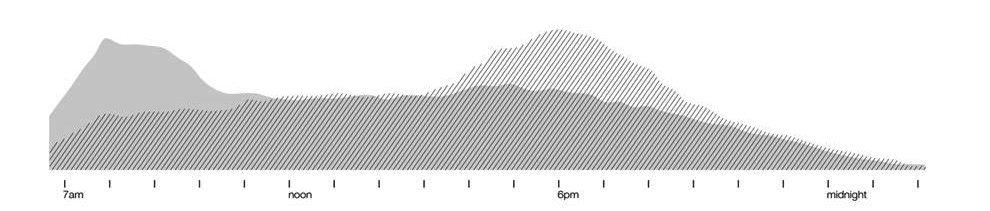

The graphs below present two fairly typical examples of visualisations charting some kind of data over time. In this case, they are the data a few of us at Microsoft Research in Cambridge have begun to collect of vehicle and bicycle journeys outside our office building. They show the volume of journeys along Tenison Road, recorded over twenty-four hours. The first indicates the density of the traffic and the second presents the direction of that traffic.

But why are we collecting this data? How and where will it circulate? And to what end? We might ask, as well, what rights we have to capture, store and present the data? Who should have rights to the data? How will it be used? In short, in what ways do the flows of traffic on Tenison Road matter, and to whom?

It’s precisely this line of questioning that has motivated our traffic-monitoring exercise and more generally a yearlong project we are embarking on with the people living and working on Tenison Road. The project — handily called the Tenison Road project — stems from some troubles we’ve had with all the excitement about data being reported by the popular press and matched by at least some of the claims coming from our technologically-minded comrades. It is hard not to open a newspaper, journal issue or conference proceedings without seeing something about data. On the one hand we have some pretty exaggerated claims envisioning data (especially Big Data) as the final answer for understanding just about anything that’s hitherto been too complex to understand. On the other, we see an abundance of stories predicting that a surveillance society afforded by the proliferation of personal data is set to dismantle civic life as we know it. Running alongside this is a discussion on appropriate policy frameworks that might enable the potential of data, while minimizing the risks and protecting the rights of citizens — encapsulated by the European Union’s focus this past year on gaining approval for the draft Data Protection Regulation.

No matter how you cut it, however, it’s abundantly clear that where data extends into the everyday — and is mobilised with many heterogeneous motives — there are some profoundly challenging technical, social and ethical issues at stake. On Tenison Road at least, we’ve found such issues to be deeply intertwined, immediately raising questions around how particular actors are prioritised and privileged and whether there may be different and possibly better ways to distribute agency. We’ve found there to be a troubling (if not altogether unsurprising) degree of nuance and complexity, and some real uncertainty about how things might be better.

Perhaps too often, Big Data — and data in general — is discussed in the abstract, and the tendency is to overlook these nuances and complexities. The impact of forms of digital data on individuals and societies are not fully understood. There is a dearth of evidence on the role of data in everyday life: how people think about it and its effects on communities and collective decision-making. In theory, better evidence should lead to improved policy making, both in its effectiveness and implementation. Practically, how this might happen is far from clear.

It is with these, if you will, ‘troubles’ in mind that we’ve planned this day of dialogue, bringing together theorists, policy makers, and commentators. The dialogues will invite provocations and controversies as ways of getting at problematic issues at the intersection of policy making, technology design and civic life. These may describe situations where the boundaries between people, technologies and concepts are vague, contested or otherwise ‘messy’. Our hope is that they will also be generative and invite insights into designing more appropriate technologies, policy frameworks and civic engagements.

The structure of the dialogue day is deliberately open so that important matters of concern can be identified collaboratively, and unravelled at length during what we’re ambitiously thinking of as ‘un-sessions’. Reports from other policy forums hint at a range of rich topics that might be significant to those of us working at the intersections of data, policy and civic life.1 Policy discussions that have focused on the interactions between different groups, such as individuals, organisations and governments, often draw on the metaphor of ‘ecosystems’. Thinking through the interplay within such systems, policy makers are challenged to mediate between the rights and responsibilities of various actors. Concepts of risk and harm are to be balanced against emerging opportunities for the production of various forms of value. Moreover, as data subjects or citizens, individuals are figured as having particular rights — most obviously to security and privacy. There are questions around how these should be balanced against the benefits to larger social groupings such as societies and nation-states.

Although a shared vocabulary is emerging in this area, many differences remain in how policy problems are understood and articulated; indeed we anticipate that participants in our dialogue day will bring along a wide range of perspectives. Rather than assuming consensus, we want to turn attention to the practice of problem-making itself. How do we currently formulate the challenges and promises of data in policy-making? How are the actors involved (such as individuals and organisations) bounded and framed? The many positions generated during the dialogue day provide an opportunity to deliberately complicate and thicken the issues. How can we learn from each other in order to pose better or different problems? How might provocations or controversies challenge us to articulate actors differently? How might engaging with the practice of problem-making in critical, inventive or speculative ways shift the concerns that emerge? How might these shifts result in better technologies, policies, and ethical systems that can help address the challenges posed?

Here at Microsoft Research, in the context of the Tenison Road project, doing problem-making differently has meant grappling with how individuals are tied together in complex ways, as part of networks, groups or communities. We have had to reflect on what citizenship might mean in the design and development of this research. Our experiences resonate with challenges in the development of data policy. We might ask what kinds of collectives are evoked by ideas of the ‘communal’ or ‘greater good’? Likewise, this research has involved assembling a diverse group of people from Tenison Road and beyond. We are constantly questioning (and being questioned about) what participation might mean, particularly as the project develops to address community concerns over time. Public participation in policy contexts is often understood as a ‘good,’ but how is participation allowed to unfold? How might we unpack phrases such as ‘citizen empowerment’? These are examples of the kinds of topics that might be raised for further discussion during the un-sessions, depending on the interests and alignments of attendees.

One of the most important outcomes of the dialogue day will be a list of questions that can set us on an appropriate course to address the objectives discussed above. We are also crafting a dynamic community of interest that can pursue the development of approaches that may potentially lead to solutions. The questions can be used to inform future meetings or events, but we hope they may generate insights that can ultimately and practically inform the development of data policy and form the bases for an active and growing community of interested parties.

The list of questions will be circulated to participants, along with a summary report that attempts to detail the discussions that took place on the day. We encourage any submissions, contributions or changes to this document. Finally, we will produce a commentary — in the form of a position paper of sorts — that fleshes out in greater depth the connections between these discussions and the questions that are emerging from the Tenison Road project. This will draw on sociological literatures, particularly those specific to the study of science and technology. We imagine that this might be one of a series of position papers and invite participants of the dialogue day to contribute. Our hope is that this will be the beginning of a continuing dialogue, hosted here at Microsoft Resarch or by others in the emerging network.

The vision of a data-rich and hyper-connected world presents some of the most challenging questions, particularly at the intersection of data, policy and civic life. We are pleased to be facilitating such a knowledgeable group of people from diverse backgrounds, to begin working through these ‘troubles’.

1Examples include:

(a) World Economic Forum reports, available here.

(b) strands of the 2013 Big Data European Conference, see here.

© the International Institute of Communications workshop on “Creating a User-Centred Data Ecosystem: Context and Policy,” see here.

More information about the Tenison Road project is available here.

This document has been authored by Lara Houston, Alex Taylor and Carolyn Nguyen.